Japan Approves Over-the-Counter Sale of Emergency Contraceptive Pill

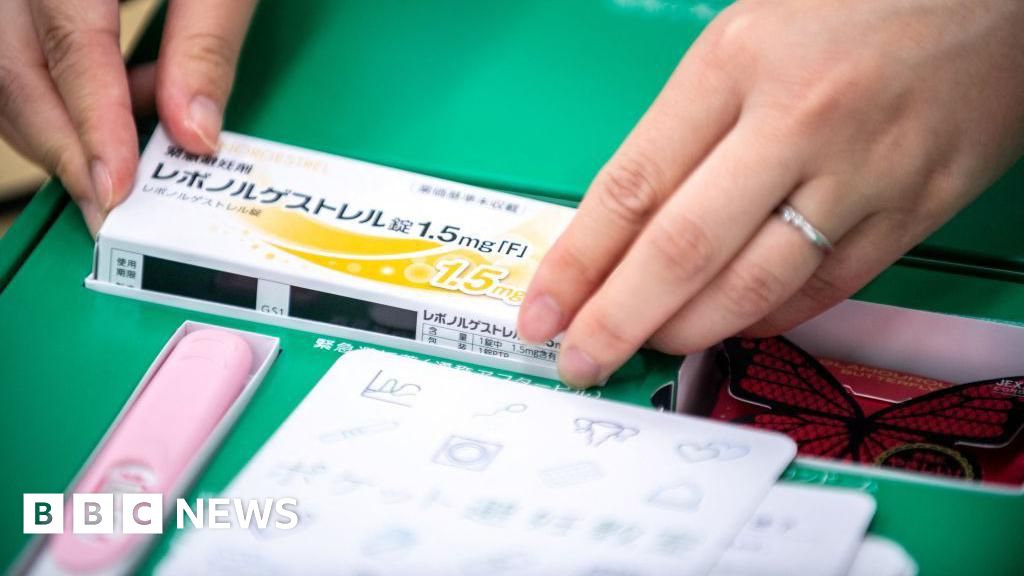

Japan has approved the over-the-counter sale of an emergency contraceptive pill for the first time, allowing women in the country to take the drug without a prescription. The manufacturer, ASKA Pharmaceutical, said wider access to the pill would empower Japanese women in the area of reproductive health. A date for the start of sales has yet to be announced.

How the Pill Will Be Sold

The pill will be labeled as a “medicine requiring advice,” meaning women must take it in the presence of a pharmacist. There are no age restrictions for buyers and no parental consent is required. The “morning after pill” – a form of emergency contraception – is already available without a prescription in more than 90 countries and is intended to prevent unwanted pregnancy.

How the Pill Works

It prevents a woman’s egg from fully developing or attaching to the uterine wall. It usually needs to be taken within three to five days of unprotected sex – but the sooner it is taken, the more effective it is. The pill, sold under the Norlevo brand, works best within 72 hours of unprotected sex and has an 80% effectiveness rate.

Background on Approval

The approval of medicines related to women’s reproductive health in Japan is slow due to the country’s conservative views, rooted in patriarchy and deeply traditional views about the role of women. ASKA Pharmaceutical sought regulatory approval in 2024 after over-the-counter trial sales of the pill the year before. During the process, Norlevo was available in 145 pharmacies in Japan. Until now, the pill was only dispensed in clinics or pharmacies after a medical examination and prescription.

Previous Discussions and Trials

Selling the drug without a prescription was first discussed by a Health Ministry panel in 2017 – the public consultation received overwhelming support across the country. However, officials didn’t give the green light at the time, saying easier availability would encourage irresponsible use of the morning-after pill. Human rights groups criticized the trial for being too small and called for the restrictions to be lifted. Activists have long argued that requiring a prescription discourages younger women and rape victims from seeking emergency contraception.